Title: The Unbroken Chain: A Beginner’s Guide to the Preservation of the Qur’an

Authors: Maaz Ahmad, Sana Amjad

Date: July 19, 2024

Publisher: Wisdom Connect

Website: www.wisdomconnect.io

Contact: info@wisdomconnect.io

Copyright Notice: © 2024 Wisdom Connect. All rights reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

For more information, visit Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors Information

Maaz Ahmad, an Indian entrepreneur, dedicates his efforts to managing his IT firm and producing scholarly articles. He established Wisdom Connect to act as an intermediary between individuals without specialized knowledge and experts in the field. Haytem Sidky and Jonathan A.C. Brown, esteemed scholars, served as a source of inspiration and influence for his scholarly endeavors.

Sana Amjad, coming from Pakistan, is a dedicated learner pursuing courses in Islamic theology and psychology. She is a psychology student pursuing her undergraduate degree and holds a Master’s degree in Islamic Studies. Her primary reason for working is to fulfill her devotion to Allah and contribute to the welfare of the Muslim community.

Abstract

Despite the Quran’s broad renown as the most preserved sacred text, many people are ignorant of its comprehensive history, from its revelation to its printing. This paper presents a thorough examination of the historical aspects of the Quranic text and specifically addresses the inquiries posed by Orientalists regarding the Quran during the past two centuries. Specifically, we analyze Orientalists who endeavor to make arguments opposing the preservation of the Quran. Initially, we will examine the historical origins of the Quranic text using trustworthy sources. Next, we will go into the history of Quranic interpretation and its intended significance. Lastly, we will tackle several problematic hadiths that are connected to the Quran. Throughout this procedure, we shall engage in a comprehensive examination of the initial manuscripts of the Quran.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, we would want to express our gratitude to Allah, the only deity. Despite my hectic schedule, I managed to write this paper. I express profound gratitude to esteemed academics including Akram Nadwi, Ali Ataie, Hafiz Muhammad Zubair, Jonathan A.C. Brown, Muhammad Mustafa Azmi, and Yasir Qadhi, whose influence has inspired me to write a fundamental piece on the preservation of the Quran. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Sana Amjad for her outstanding contributions in the field of Arabic texts, tafsir, and early liturgies. Her assistance was crucial in enabling me to publish and complete it within the current timeframe. I express my heartfelt gratitude to Sarmad Chauhadry for his encouragement in the development of platforms such as Wisdom Connect, which aims to facilitate communication between ordinary individuals and intellectuals.

Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude to Seema Qaiser for her exceptional recommendations and unwavering assistance. The feedback she provided was really valuable in simplifying the article for anyone without specialized knowledge.

The Quran

The Quran is widely defined in various ways, but these differences are merely in wording, not in meaning. A suitable definition is: The Quran is the Arabic speech of Allah, revealed to Muhammad (PBUH) in both word and meaning, which has been preserved in written form (Mushafs), transmitted through reliable, numerous chains (mutawatir), and challenged humanity to produce something comparable.

Details of this Definition

The Quran is Allah’s Arabic speech.

- Quran [12:2] ‘إِنَّآ أَنزَلْنَـٰهُ قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا لَّعَلَّكُمْ تَعْقِلُونَ’ “Indeed, We have sent it down as an Arabic Quran that you might understand.”

- Quran [20:113] ‘وَكَذَٰلِكَ أَنزَلْنَـٰهُ قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا وَصَرَّفْنَا فِيهِ مِنَ ٱلْوَعِيدِ لَعَلَّهُمْ يَتَّقُونَ أَوْ يُحْدِثُ لَهُمْ ذِكْرًۭا’ “And thus We have sent it down as an Arabic Quran and have diversified therein the warnings that perhaps they will avoid [sin] or it would cause them remembrance.”

- Quran [26:195] ‘بِلِسَانٍ عَرَبِىٍّۢ مُّبِينٍۢ’ “In a clear Arabic language.”

- Quran [16:103] ‘وَلَقَدْ نَعْلَمُ أَنَّهُمْ يَقُولُونَ إِنَّمَا يُعَلِّمُهُۥ بَشَرٌۭ ۗ لِّسَانُ ٱلَّذِى يُلْحِدُونَ إِلَيْهِ أَعْجَمِىٌّۭ وَهَـٰذَا لِسَانٌۭ عَرَبِىٌّۭ مُّبِينٌ’ “And We certainly know that they say, ‘It is only a human being who teaches him.’ The tongue of the one they refer to is foreign, and this [recitation] is in clear Arabic.”

- Quran [39:28] ‘قُرْءَانًۭا عَرَبِيًّۭا غَيْرَ ذِى عِوَجٍۢ لَّعَلَّهُمْ يَتَّقُونَ’ “[It is] an Arabic Quran, without any deviance that they might become righteous.”

- Quran [41:3] ‘كِتَـٰبٌۭ فُصِّلَتْ ءَايَـٰتُهُۥ قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا لِّقَوْمٍۢ يَعْلَمُونَ’ “[It is] a Book whose verses have been detailed, an Arabic Quran for people who know.”

- Quran [42:7] ‘وَكَذَٰلِكَ أَوْحَيْنَآ إِلَيْكَ قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا لِّتُنذِرَ أُمَّ ٱلْقُرَىٰ وَمَنْ حَوْلَهَا وَتُنذِرَ يَوْمَ ٱلْجَمْعِ لَا رَيْبَ فِيهِ ۚ فَرِيقٌۭ فِى ٱلْجَنَّةِ وَفَرِيقٌۭ فِى ٱلسَّعِيرِ’ “And thus We have revealed to you an Arabic Quran that you may warn the mother of Cities and those around it and warn of the Day of Assembly, about which there is no doubt. A party will be in Paradise, and a party will be in the Blaze.”

- Quran [43:3] ‘إِنَّا جَعَلْنَـٰهُ قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا لَّعَلَّكُمْ تَعْقِلُونَ’ “Indeed, We have made it an Arabic Quran that you might understand.”

- Quran [46:12] ‘وَمِن قَبْلِهِۦ كِتَـٰبُ مُوسَىٰٓ إِمَامًۭا وَرَحْمَةًۭ ۚ وَهَـٰذَا كِتَـٰبٌۭ مُّصَدِّقٌۭ لِّسَانًا عَرَبِيًّۭا لِّيُنذِرَ ٱلَّذِينَ ظَلَمُوا۟ وَبُشْرَىٰ لِلْمُحْسِنِينَ’ “And before it was the Scripture of Moses to lead and as a mercy. And this is a confirming Book in an Arabic tongue to warn those who have wronged and as good tidings to the doers of good.”

- Quran [13:37] ‘وَكَذَٰلِكَ أَنزَلْنَـٰهُ حُكْمًا عَرَبِيًّۭا ۚ وَلَئِنِ ٱتَّبَعْتَ أَهْوَآءَهُم بَعْدَ مَا جَآءَكَ مِنَ ٱلْعِلْمِ مَا لَكَ مِنَ ٱللَّهِ مِن وَلِىٍّۢ وَلَا وَاقٍ’ “And thus We have revealed it as an Arabic legislation. And if you should follow their inclinations after what has come to you of knowledge, you would not have against Allah any ally or any protector.”

- Quran [19:97] ‘فَإِنَّمَا يَسَّرْنَـٰهُ بِلِسَانِكَ لِتُبَشِّرَ بِهِ ٱلْمُتَّقِينَ وَتُنذِرَ بِهِۦ قَوْمًۭا لُّدًّۭا’ “So, [O Muhammad], We have only made it easy in your tongue that you may give good tidings thereby to the righteous and warn thereby a hostile people.”

- Quran [44:58] ‘فَإِنَّمَا يَسَّرْنَـٰهُ بِلِسَانِكَ لَعَلَّهُمْ يَتَذَكَّرُونَ’ “And indeed, We have eased the Quran in your tongue that they might be reminded.”

This means that any translation of the Quran cannot be considered a Quran. Imam az-Zarkashee asserted that the revelation of the Quran took place in Arabic, thereby prohibiting its recitation in any other language, and Ibn Qudama also says in Al-Mughni that reciting in a non-Arabic language will not be sufficient, nor will reciting the Arabic words of the Quran by replacing them with other words of the Arabic language, whether he knows Arabic or not.

Muhammad (PBUH) received the Quran’s words and meaning.

Verses Emphasizing Words of Revelation

- Quran [53:3-4] ‘وَمَا يَنطِقُ عَنِ ٱلْهَوَىٰٓ. إِنْ هُوَ إِلَّا وَحْىٌۭ يُوحَىٰ’ “Nor does he speak from [his own] inclination. It is nothing except a revelation revealed.”

- Quran [75:16-18] ‘لَا تُحَرِّكْ بِهِۦ لِسَانَكَ لِتَعْجَلَ بِهِۦٓ. إِنَّ عَلَيْنَا جَمْعَهُۥ وَقُرْءَانَهُۥ. فَإِذَا قَرَأْنَـٰهُ فَٱتَّبِعْ قُرْءَانَهُۥ’ “Do not move your tongue with it to hasten it. Indeed, upon Us is its collection [in your heart] and [to make possible] its recitation. So, when We have recited it [through Gabriel], then follow its recitation.”

- Quran [87:6] ‘سَنُقْرِئُكَ فَلَا تَنسَىٰٓ’ “We will make you recite [O Muhammad], and you will not forget.”

- Quran [15:9] ‘إِنَّا نَحْنُ نَزَّلْنَا ٱلذِّكْرَ وَإِنَّا لَهُۥ لَحَـٰفِظُونَ’ “Indeed, it is We who sent down the Quran, and indeed, We will be its guardian.”

Verses Emphasizing the Meanings of Revelation:

- Quran [75:19] ‘ثُمَّ إِنَّ عَلَيْنَا بَيَانَهُۥ’ “Then upon Us is its clarification [to you].”

- Quran [16:44] ‘بِٱلْبَيِّنَـٰتِ وَٱلزُّبُرِ ۗ وَأَنزَلْنَآ إِلَيْكَ ٱلذِّكْرَ لِتُبَيِّنَ لِلنَّاسِ مَا نُزِّلَ إِلَيْهِمْ وَلَعَلَّهُمْ يَتَفَكَّرُونَ’ “[We sent them] with clear proofs and written ordinances. And We revealed to you the message that you may make clear to the people what was sent down to them and that they might give thought.”

- Quran [6:19] ‘قُلْ أَىُّ شَىْءٍ أَكْبَرُ شَهَـٰدَةًۭ ۖ قُلِ ٱللَّهُ ۖ شَهِيدٌۢ بَيْنِى وَبَيْنَكُمْ ۚ وَأُوحِىَ إِلَىَّ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانُ لِأُنذِرَكُم بِهِۦ وَمَنۢ بَلَغَ ۚ أَئِنَّكُمْ لَتَشْهَدُونَ أَنَّ مَعَ ٱللَّهِ ءَالِهَةًۭ أُخْرَىٰ ۚ قُل لَّآ أَشْهَدُ ۚ قُلْ إِنَّمَا هُوَ إِلَـٰهٌۭ وَٰحِدٌۭ وَإِنَّنِى بَرِىٓءٌۭ مِّمَّا تُشْرِكُونَ’ “Say, ‘What thing is the greatest as a testimony?’ Say, ‘Allah is witness between me and you. And this Quran was revealed to me that I may warn you thereby and whomever it reaches. Do you [truly] testify that with Allah there are other deities?’ Say, ‘I will not testify [with you].’ Say, ‘Indeed, He is but one God, and indeed, I am free of what you associate [with Him].'”

- Quran [4:113] ‘وَلَوْلَا فَضْلُ ٱللَّهِ عَلَيْكَ وَرَحْمَتُهُۥ لَهَمَّت طَّآئِفَةٌۭ مِّنْهُمْ أَن يُضِلُّوكَ وَمَا يُضِلُّونَ إِلَّآ أَنفُسَهُمْ وَمَا يَضُرُّونَكَ مِن شَىْءٍۢ ۚ وَأَنزَلَ ٱللَّهُ عَلَيْكَ ٱلْكِتَـٰبَ وَٱلْحِكْمَةَ وَعَلَّمَكَ مَا لَمْ تَكُن تَعْلَمُ ۚ وَكَانَ فَضْلُ ٱللَّهِ عَلَيْكَ عَظِيمًۭا’ “And if it were not for the favor of Allah upon you, [O Muhammad], and His mercy, a group of them would have been determined to mislead you. But they do not mislead except themselves, and they will not harm you at all. And Allah has revealed to you the Book and wisdom and has taught you that which you did not know. And ever has the favor of Allah upon you been great.”

- Quran [2:151] ‘كَمَآ أَرْسَلْنَا فِيكُمْ رَسُولًۭا مِّنكُمْ يَتْلُوا۟ عَلَيْكُمْ ءَايَـٰتِنَا وَيُزَكِّيكُمْ وَيُعَلِّمُكُمُ ٱلْكِتَـٰبَ وَٱلْحِكْمَةَ وَيُعَلِّمُكُم مَّا لَمْ تَكُونُوا۟ تَعْلَمُونَ’ “Just as We have sent among you a messenger from yourselves reciting to you Our verses and purifying you and teaching you the Book and wisdom and teaching you that which you did not know.”

Verses Emphasizing Both Words and Meanings of Revelation:

- Quran [20:114] ‘فَتَعَـٰلَى ٱللَّهُ ٱلْمَلِكُ ٱلْحَقُّ ۗ وَلَا تَعْجَلْ بِٱلْقُرْءَانِ مِن قَبْلِ أَن يُقْضَىٰٓ إِلَيْكَ وَحْيُهُۥ وَقُل رَّبِّ زِدْنِى عِلْمًۭا’ “So high [above all] is Allah, the Sovereign, the Truth. And, [O Muhammad], do not hasten with [recitation of] the Quran before its revelation is completed to you, and say, ‘My Lord, increase me in knowledge.'”

- Quran [2:97] ‘قُلْ مَن كَانَ عَدُوًّۭا لِّجِبْرِيلَ فَإِنَّهُۥ نَزَّلَهُۥ عَلَىٰ قَلْبِكَ بِإِذْنِ ٱللَّهِ مُصَدِّقًۭا لِّمَا بَيْنَ يَدَيْهِ وَهُدًۭى وَبُشْرَىٰ لِلْمُؤْمِنِينَ’ “Say, ‘Whoever is an enemy to Gabriel—it is [none but] he who has brought it [the Quran] down upon your heart, [O Muhammad], by permission of Allah, confirming that which was before it and as guidance and good tidings for the believers.'”

These verses collectively indicate that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) received the Quran both in its verbal form (words) and in its intended meanings.

The Quran has been preserved in written form (Mushafs) and transmitted through reliable, numerous chains (mutawatir).

The literal meaning of Mushafs is a collection of pages or a compiled book. In the Quranic context, it refers to a written or printed copy of the Quran. The Quran, which was written at the time of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), was compiled at the time of Abu Bakr and standardized at the time of Uthman Ibn Affan. Which contains 114 surahs from Surah al-Fatiha to Surah an-Naas.

Furthermore, “…and has reached us by mutawatir transmissions…” means the Quran was transmitted through numerous reliable narrations across generations, ensuring its authenticity.

Challenging humanity to produce something comparable.

- Quran [17:88]قُل لَّئِنِ ٱجْتَمَعَتِ ٱلْإِنسُ وَٱلْجِنُّ عَلَىٰٓ أَن يَأْتُوا۟ بِمِثْلِ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانِ لَا يَأْتُونَ بِمِثْلِهِۦ وَلَوْ كَانَ بَعْضُهُمْ لِبَعْضٍۢ ظَهِيرًۭا”Say, ‘If all of humankind and jinn were to come together to produce the like of this Quran, they could not produce the like of it, even if they were to each other’s assistants.'”

- Quran [10:38]أَمْ يَقُولُونَ ٱفْتَرَىٰهُ ۖ قُلْ فَأْتُوا۟ بِسُورَةٍۢ مِّثْلِهِۦ وَٱدْعُوا۟ مَنِ ٱسْتَطَعْتُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ”Or do they say, ‘He fabricated it?’ Say, ‘Then bring forth a surah like it, and call upon whomever you can besides Allah if you should be truthful.'”

- Quran [11:13]أَمْ يَقُولُونَ ٱفْتَرَىٰهُ ۖ قُلْ فَأْتُوا۟ بِعَشْرِ سُوَرٍۢ مِّثْلِهِۦ مُفْتَرَيَـٰتٍۢ وَٱدْعُوا۟ مَنِ ٱسْتَطَعْتُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ”Or do they say, ‘He invented it’? Say, ‘Then bring ten surahs like it that have been invented, and call upon whomever you can besides Allah, if you should be truthful.'”

- Quran [2:23]وَإِن كُنتُمْ فِى رَيْبٍۢ مِّمَّا نَزَّلْنَا عَلَىٰ عَبْدِنَا فَأْتُوا۟ بِسُورَةٍۢ مِّن مِّثْلِهِۦ وَٱدْعُوا۟ شُهَدَآءَكُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ”And if you are in doubt about what We have sent down upon Our Servant, then produce a surah the like thereof and call upon your witnesses other than Allah, if you should be truthful.”

- Quran [52:33–34]أَمْ يَقُولُونَ تَقَوَّلَهُۥ ۚ بَل لَّا يُؤْمِنُونَ. فَلْيَأْتُوا۟ بِحَدِيثٍۢ مِّثْلِهِۦٓ إِن كَانُوا۟ صَـٰدِقِينَ”Or do they say, ‘He has made it up’? Rather, they do not believe. Let them produce a statement like it if they should be truthful.”

These verses present a clear and open challenge to humanity, emphasizing the miraculous nature (ijazz) of the Quran. Despite various efforts throughout history, no one has succeeded in producing a text comparable in eloquence, depth, and guidance, and when we say Quran, it means it can be both the entire text and any part of it.

Uloom al-Quran

‘Uloom al-Quran, or ‘The Sciences of the Quran,’ encompasses the study of various disciplines directly related to the Quran’s recitation, history, comprehension, and application. This extensive field of Islamic scholarship holds significant importance.

In terms of the Quran’s history, ‘Uloom al-Quran covers the stages of its revelation, its compilation, the art and history of writing Quranic script (rasm al-masahif), and its preservation.

For understanding and implementing the Quran, ‘Uloom al-Quran includes the causes of revelation (Asbaab an-nuzool.[1]), the knowledge of Meccan and Medinan revelations[2], the forms (Ahruf[3]) in which it was revealed, understanding abrogated rulings and verses (naasikh wa al-mansookh[4]), the classifications of its verses (Muhkam and Mutashabih[5], ‘aam and Khaas[6], mutlaq and muqayyad[7]), the inimitable style of the Quran (i’jaz al-Quran[8]), interpretation (Tafseer[9]), grammatical analysis (I’rab al-Quran[10]), and uncommon words (Ghareeb al-Quran[11]).

The History of Uloom al-Quran

Like other Islamic sciences, Uloom al-Quran started with the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), from whose life we have several examples. It then continued with the Companions, the Successors, and the Successors’ successors, among other things.

Examples from the Life of the Prophet:

Explanation of Difficult Words

- Understanding Specific Words:

‘وَعَاشِرُوهُنَّ بِٱلْمَعْرُوفِ’ Quran [4:19]

“And live with them in kindness.”

When this verse was revealed, the Prophet explained “بِٱلْمَعْرُوفِ” (in kindness) by advising men to treat their wives with respect and kindness. He said:

“The best of you are those who are best to their wives.”[12]

Contextualizing Revelations

- Context of Revelation (Asbab al-Nuzul):

‘لَّيْسَ ٱلْبِرَّ أَن تُوَلُّوا۟ وُجُوهَكُمْ قِبَلَ ٱلْمَشْرِقِ وَٱلْمَغْرِبِ’ Quran [2:177]

“Righteousness is not that you turn your faces toward the east or the west, but [true] righteousness is in one who believes in Allah, the Last Day, the Angels, the Book, and the Prophets…”

When this verse was revealed, the Companions were concerned about the correct direction of prayer. The Prophet explained that true righteousness is not about the direction of prayer but about one’s faith and actions, clarifying:

“Righteousness is in good character, and sin is what wavers in your heart and you do not want people to know about it.”[13]

Clarification of General Statements

- Clarifying Ambiguous Verses:’وَكُلُوا۟ وَٱشْرَبُوا۟ حَتَّىٰ يَتَبَيَّنَ لَكُمُ ٱلْخَيْطُ ٱلْأَبْيَضُ مِنَ ٱلْخَيْطِ ٱلْأَسْوَدِ’ Quran [2:187] “And eat and drink until the white thread of dawn becomes distinct to you from the black thread [of night].”When this verse was revealed, some Companions took this literally and tied white and black threads to determine the start of fasting. The Prophet clarified that it meant the white and black of dawn, as explained:”It is your whiteness and blackness of dawn.”[14]

Illustrating the Depth of Verses

- Deeper Meanings and Implications:

‘يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ لَا تَسْأَلُوا۟ عَنْ أَشْيَآءَ إِن تُبْدَ لَكُمْ تَسُؤْكُمْ’ Quran [5:101]

“O, you who have believed, do not ask about things which, if they are shown to you, will distress you.”

The Prophet advised the Companions to avoid excessive questioning that could lead to hardship. He said:

“Allah has enjoined certain obligations, so do not neglect them; He has forbidden certain things, so do not commit them; He has laid down certain limits, so do not transgress them; and He has remained silent about certain things out of mercy for you, not out of forgetfulness, so do not search for them.”[15]

Practical Application of Verses

- Practical Guidance:

‘يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ إِذَا نُودِىَ لِلصَّلَوٰةِ مِن يَوْمِ ٱلْجُمُعَةِ فَٱسْعَوْا۟ إِلَىٰ ذِكْرِ ٱللَّهِ’

“O, you who have believed, when [the adhan] is called for the prayer on the day of Jumu’ah [Friday], then proceed to the remembrance of Allah…” Quran [62:9]

When this verse was revealed, the Prophet emphasized the importance of leaving trade and attending the Jumu’ah prayer, reinforcing communal worship. He said:

“The best day on which the sun has risen is Friday; on it, Adam was created.”[16]

Addressing Misunderstandings

- Correcting Misinterpretations:

When some people misunderstand the verse:

‘ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ وَلَمْ يَلْبِسُوٓا۟ إِيمَـٰنَهُم بِظُلْمٍ’

“Those who believe and do not mix their belief with injustice…” Quran [6:82]

People thought it meant any form of sin, the Prophet clarified that “ظُلْمٍ” referred specifically to shirk, as he explained:

“It is not as you all think, it is only shirk (that is meant by ظلم here). Have you not heard what Luqman said to his son: ‘Verily, shirk is a great ظلم (wrongdoing)?'”[17]

Historical and Situational Context

- Revealing Historical Contexts:

When the verse was revealed during the farewell pilgrimage;

‘ٱلْيَوْمَ أَكْمَلْتُ لَكُمْ دِينَكُمْ’ Quran [5:3]

The Prophet ﷺ inquired on the occasion of Hujtul wida: If you are going to be asked about me, what will you say? The Companions said: We bear witness that you (PBUH) preached, conveyed the message, and fulfilled the right of benevolence.

Hearing this, the Prophet (PBUH) raised his index finger towards the sky and bowed to the people, and said three times: O Allah, be a witness, O Allah, be a witness, O Allah, be a witness.[18]

- Encouraging Tafakkur (Reflection):

When the verse was revealed:

‘إِنَّ فِى خَلْقِ ٱلسَّمَـٰوَٰتِ وَٱلْأَرْضِ وَٱخْتِلَـٰفِ ٱلَّيْلِ وَٱلنَّهَارِ لَءَايَـٰتٍ لِّأُو۟لِى ٱلْأَلْبَـٰبِ’ Quran [3:190]

“Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and the earth and the alternation of the night and the day are signs for those of understanding.”

The Prophet emphasized the importance of pondering over the creation of the heavens and the earth, encouraging the Companions to reflect deeply on Allah’s signs. He often recited this verse during his night prayers, as mentioned in the Hadith:

“The Prophet recited these verses when he got up to pray at night.”[19]

Ibn Mas’ood’s Dedication

Ibn Masud was one of the earliest converts to Islam and was known for his profound knowledge of the Quran. He said:

“By Allah, besides whom there is no other god, there is no surah in the Quran except that I know where it was revealed, and there is no verse except that I know the reason for its revelation. If anyone knew more about the Quran than I do and I could reach him, I would travel to seek that knowledge.”[20]

Contributions of ibn Masud:

- Teaching: He taught the Quran and its meanings extensively, influencing many later scholars. His student, Alqamah ibn Qays, became a prominent scholar in Kufa.

- Recitation: The Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) specifically praised his recitation, saying:Narrated Aisha: The Prophet said, Such a person as recites the Qur’an and masters it by heart, will be with the noble righteous scribes (in Heaven). And such a person exerts himself to learn the Qur’an by heart, and recites it with great difficulty, will have a double reward.[21]

Ibn Abbas’s Dedication;

Ibn Abbas was known as “Tarjuman al-Quran” (Interpreter of the Quran). He was a cousin of the Prophet and was highly regarded for his deep understanding of the Quran.

Contributions:

- Tafsir: Ibn Abbas’s explanations of the Quran were compiled by his students and later became foundational for many tafsir works. His Tafsir has been transmitted through various chains, such as that of Mujahid, Ikrimah, and Ata’ ibn Abi Rabah.

- Hadith: Ibn Abbas narrated numerous Hadiths that provided context for Quranic verses. For instance, he narrated the explanation of the verse:

‘إِذَا جَآءَ نَصْرُ ٱللَّهِ وَٱلْفَتْحُ’

“When the victory of Allah has come and the conquest,” Quran [110:1]

He said; it indicated the nearing of the Prophet’s death.[22]

Umar ibn Al-Khattab’s Dedication;

Umar ibn Al-Khattab was the second Caliph of Islam and was known for his just and strong leadership. He deeply engaged with the Quran and often sought to understand its deeper meanings.

Contributions:

- Consultations with Ibn Abbas: Umar frequently consulted Ibn Abbas for explanations of Quranic verses, highlighting the importance of tafsir. An example is his inquiry about the verse:

‘إِنَّا أَعْطَيْنَاكَ ٱلْكَوْثَرَ’

“Indeed, We have granted you, [O Muhammad], al-Kawthar.” Quran [108:1]

Ibn Abbas explained that “al-Kawthar” refers to a river in Paradise.[23]

- Implementation of Quranic Principles: Umar’s caliphate was marked by his implementation of Quranic principles in governance and justice, ensuring the laws were aligned with Islamic teachings.

Aisha’s Dedication;

Aisha, the wife of the Prophet, was one of the most knowledgeable Companions regarding the Quran and Hadith. She provided significant insights into many Quranic revelations.

Contributions:

- Narration of Contexts: Aisha narrated the context of several revelations, such as explaining the background of the verse:

‘وَإِذْ تَقُولُ لِلَّذِيٓ أَنعَمَ ٱللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَأَنعَمْتَ عَلَيْهِ أَمْسِكْ عَلَيْكَ زَوْجَكَ وَٱتَّقِ ٱللَّهَ’ Quran [33:37]

“And [remember, O Muhammad], when you said to the one on whom Allah bestowed favor and you bestowed favor, ‘Keep your wife and fear Allah,’…” involving Zayd ibn Harithah and Zaynab bint Jahsh.[24]

- Teaching: She taught many students, including Urwah ibn Zubayr and Al-Qasim ibn Muhammad, who transmitted her knowledge to future generations.

Abdullah ibn Umar’s Dedication;

Abdullah ibn Umar was known for his strict adherence to the Sunnah and his deep engagement with the Quran.

Contributions:

- Narration of Revelation Contexts: Abdullah ibn Umar narrated the gradual prohibition of alcohol, explaining the verse:’يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوا۟ لَا تَقْرَبُوا۟ ٱلصَّلَوٰةَ وَأَنتُمْ سُكَـٰرَىٰ حَتَّىٰ تَعْلَمُوا۟ مَا تَقُولُونَ’ Quran [4:43]

“O, you who have believed, do not approach prayer while you are intoxicated until you know what you are saying…”

He narrated that the prophet said; Allah has cursed wine, its drinker, its server, its buyer, its preserver, the one for who conveys it and the one to whom it is conveyed.[25]

- Practice: He meticulously followed the Prophet’s actions, ensuring that his practices were in line with the Quran and Sunnah, such as performing Hajj multiple times and documenting the Prophet’s practices during it.

Ali ibn Abi Talib’s Dedication;

Ali ibn Abi Talib was known for his wisdom and deep understanding of the Quran. He was the fourth Caliph and a close relative of the Prophet.

Ali’s Challenge

‘Ali ibn Abi Talib told his students, “Ask me about the Book of Allah, for there is no verse in it but I know whether it was revealed by night or by day, on the plains or in the mountains.[26]

Contributions:

- Explanation of Verses:

Abdul Malik bin Abi Sulaiman says; I asked Atta Was there anyone among the companions of the prophet more knowledgeable than Ali? He said; No, by God I do not know anyone other than him (Ali ibn Abi Talib).[27]

- Solving complicated problems;

Umar bin Al-Khattab used to seek refuge from Allah from the complicated problems whose solution was not found by Ali ibn Abi Talib.[28]

Saeed bin Jubiar said; that when we get proof of something from Ali ibn Abi Talib then we do not turn to anyone else.[29]

Numerous companions were renowned for their profound understanding of the Quran such as;

- The Four Khulafa ar-Rashidun

- Abdullah ibn Masood (d. 32 A.H.)

- Abdullah ibn Abbas (d. 68 A.H.)

- Ubay ibn Ka’b (d. 29 A.H.)

- Zayd ibn Thaabit (d. 45 A.H.)

- Abu Musa al-Ashari (d. 44 A.H.)

- Abdullah ibn Zubayr (d. 73 A.H.)

- Maaz bin Jabal (d. 18 A.H.)

- Aishah (d. 57 A.H.)

The generation that came after the Companions, the Successors, studied eagerly under the wise guardianship of the Companions. These students took over their predecessors’ responsibilities and passed this knowledge faithfully on to the next generation.

Ibn Abbas’s students

- Sa’eed ibn Jubayr (d. 95 A.H.)

- Mujaahid ibn Jabr (d. 100 A.H.)

- Ikrimah al-Barbaree (d. 104 A.H.)

- Taawoos ibn Kaysaan (d. 106 A.H.)

- Ata’ ibn Rabah (d. 114 A.H.)

They were all famous in Makkah.

Ubay ibn Kaab’s students

- Zayd ibn Aslam (d. 63 A.H.)

- Abu al-‘Aliyah (d. 90 A.H.)

- Muhammad ibn Ka’b (d. 120 A.H.)

They were the teachers of Madinah; and in Iraq,

Abdullah ibn Masood’s students

- Alqamah ibn Qays (d. 60 A.H.)

- Masrooq ibn al-Ajda’ (d. 63 A.H.)

- Al-Hasan al-Basree (d. 110 A.H)

- Qataadah as-Sadoosee (d. 110 A.H.)

Makkah, Madinah, Kufah, and Basra, were the leading centers of all the sciences of Islam, including Tafseer and Uloom al-Quran.

History of Preservation

The compilation of the Quran is a unique phenomenon that is peculiar to Islamic history, for no other religious book can claim to be anywhere near as authentic as the Quran. Jews, Christians, and Hindus are just a few examples of religious groups whose texts are no longer in existence, whereas the Quran has both text and meaning preserved.

Allah has taken it upon Himself to guard it and protect it, for He says,

اِنَّا نَحۡنُ نَزَّلۡنَا الذِّكۡرَ وَاِنَّا لَهٗ لَحٰـفِظُوۡنَ

«Verily, We have sent down this memory (the Quran), and We are of

a surety going to protect it (from tampering) Quran [15:9]

لَا تُحَرِّكۡ بِهٖ لِسَانَكَ لِتَعۡجَلَ بِهٖؕ —اِنَّ عَلَيۡنَا جَمۡعَهٗ وَقُرۡاٰنَهٗۚ ۖ،

Do not move your tongue with haste concerning it! It is for Us to collect it and give you the ability to recite it» Quran [75:17]

The only divinely revealed text that Allah has promised to preserve is the Quran. The responsibility of preserving earlier Scriptures had been placed upon its recipients, without any divine aid. Allah mentions, concerning the earlier Scriptures,

والرَّبَّانِيُّوۡنَ وَالۡاَحۡبَارُ بِمَا اسۡتُحۡفِظُوۡا مِنۡ كِتٰبِ اللّٰهِ وَكَانُوۡا عَلَيۡهِ شُهَدَآءَ ۚ

« … and the rabbis and the priests (judged according to their Scriptures), for

to them was entrusted the protection of the Book of Allah, and they were wit-

nesses to it … » Quran [5:44]

and it is also mentioned that the Scriptures of Jews and Christians were changed.

Whether you are a Muslim or not, if you study the history of the Quran and present copies, you will agree with Muslims today that it is the same Quran as it was during the Prophet’s time.

Let’s start by looking at the history of the Quran’s preservation, followed by an examination of its transmission method and the written copies from the time of Muhammad (PBUH) to the present day.

We will divide the history of the Quran’s preservation into three sections:

- First; during the life of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH),

- Second; the compilation of the Quran by Abu Bakr

- Third; the compilation of ‘Uthman.

During the Prophet’s Life

The Prophet was sent to an illiterate nation, and he himself was the unlettered prophet, as the Quran says:

هُوَ الَّذِىۡ بَعَثَ فِى الۡاُمِّيّٖنَ رَسُوۡلًا مِّنۡهُمۡ يَتۡلُوۡا عَلَيۡهِمۡ اٰيٰتِهٖ وَيُزَكِّيۡهِمۡ وَيُعَلِّمُهُمُ الۡكِتٰبَ وَالۡحِكۡمَةَ وَاِنۡ كَانُوۡا مِنۡ قَبۡلُ لَفِىۡ ضَلٰلٍ مُّبِيۡنٍۙ

«He is the one Who has sent among the illiterate ones a Messenger from

among themselves, who will recite to them His signs, and purify them,

and teach them the Book, and the Wisdom; and before this, they were in-

deed in manifest error» Quran [62:2]

قُلۡ يٰۤاَيُّهَا النَّاسُ اِنِّىۡ رَسُوۡلُ اللّٰهِ اِلَيۡكُمۡ جَمِيۡعَاْ ۨالَّذِىۡ لَهٗ مُلۡكُ السَّمٰوٰتِ وَالۡاَرۡضِۚ لَاۤ اِلٰهَ اِلَّا هُوَ يُحۡىٖ وَيُمِيۡتُ فَاٰمِنُوۡا بِاللّٰهِ وَرَسُوۡلِهِ النَّبِىِّ الۡاُمِّىِّ الَّذِىۡ يُؤۡمِنُ بِاللّٰهِ وَكَلِمٰتِهٖ وَاتَّبِعُوۡهُ لَعَلَّكُمۡ تَهۡتَدُوۡنَ

Say, [O Muḥammad], “O mankind, indeed I am the Messenger of Allah to you all, [from Him] to whom belongs the dominion of the heavens and the earth. There is no deity except Him; He gives life and causes death.” So, believe in Allah and His Messenger, the unlettered prophet, who believes in Allah and His words, and follow him that you may be guided. Quran [7:158]

اَ لَّذِيۡنَ يَتَّبِعُوۡنَ الرَّسُوۡلَ النَّبِىَّ الۡاُمِّىَّ

«Those who follow the unlettered prophet … Quran [7:157]

The fact that the Prophet could neither read nor write was meant to be one of the greatest proofs that the Quran was not from him, but rather from the Creator Himself. If Muhammad (PBUH) was illiterate, then from where did he bring forth the literary masterpiece of the Quran? The Quran itself says:

وَمَا كُنۡتَ تَـتۡلُوۡا مِنۡ قَبۡلِهٖ مِنۡ كِتٰبٍ وَّلَا تَخُطُّهٗ بِيَمِيۡنِكَ اِذًا لَّارۡتَابَ الۡمُبۡطِلُوۡنَ

«Neither did you (O Muhammad (PBUH)) read any book before it (i.e., the revelation of the Quran) nor did you write (any book) with your right hand! In that case, indeed, the followers of falsehood might have doubted» Quran [29:48].

In other words, if the Prophet had been a writer, and one whom the people knew to be an eloquent author, this might have given reason to doubt the Prophet’s claim of prophethood; but since the Prophet was illiterate, and well-known to be so, then such a doubt could not exist!

The Quran consistently refers to itself as kitab (Book) as something written, indicating that it must be placed into written form. Verses were recorded from the earliest stages of Islam, even as the fledgling community suffered innumerable hardships under the wrath of Quraish. The following narration concerning ‘Umar bin al-Khattab, taken just before his conversion to Islam, helps illustrate this point:

One day ‘Umar came out, his sword unsheathed, intending to make for the Prophet and some of his Companions who (he had been told) were gathered in a house at as-Safi. The congregation numbered forty, including women; also present were the Prophet’s uncle Hamza, Abii Bakr, ‘Ali, and others who had not migrated to Ethiopia. Nu‘aim encountered Umar and asked him where he was going. “I am making for Muhammad, the apostate who has split Quraish asunder and mocked their ways, who has insulted their beliefs and their gods, to kill him.” “You only deceive yourself, “Umar,” he replied, “if you suppose that Bani ‘Abd Manaf will allow you to continue treading the earth if you dispose of Muhammad. Is it not better that you return to your family and resolve their affairs?” ‘Umar was taken aback and asked what was the matter with his family. Nu‘aim said, “Your brother-in-law, your nephew Sa‘id, and your sister Fatima have followed Muhammad in his new religion, and it is best that you go and deal with them.” ‘Umar hurried to his brother-in-law’s house, where Khabbab was reciting Surah Taha to them from a parchment. At the sound of Umar’s voice, Khabbab hid in a small room, while Fatima took the parchment and placed it under her thigh.[30]

Beginning of Wahy

The process of preparing the prophet for his role started from the very beginning of his childhood. The presence of Angel Jibree could be perceived from the historical references where the Angel Jibreel started to appear before the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).[31]

The first appearance of angel Jibreel was in the home of Halima bint Abi Zwaib, where the incidence of the splitting of the heart took place.[32]

Before the revelation, the signs of prophethood started in the form of true dreams, as reported by Ayesha; she said, the commencement of the divine revelation to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) started in the form of righteous dreams in his sleep. Every dream of mine came true like a bright day.[33]

In that time, the prophet used to go to the cave of Hira with some food and water in solitude to worship Allah continuously for some days and nights, then he would come back to his wife Khadijah to take some food and water again for further days and nights.

This was the time when suddenly one day the angel Jibreel descended upon the prophet, as reported in a hadith; the prophet said this when he was in the cave of Hira, and the angel asked him to read it. The prophet replied I do not know how to read. The Prophet further added that the angel caught me mightily and pressed hard so that I could not bear it and then the angel released me. (The same argument happened three times.).

Then the angel said;

اِقۡرَاۡ بِاسۡمِ رَبِّكَ الَّذِىۡ خَلَقَۚ—خَلَقَ الۡاِنۡسَانَ مِنۡ عَلَقٍۚ—اِقۡرَاۡ وَرَبُّكَ الۡاَكۡرَمُۙ—الَّذِىۡ عَلَّمَ بِالۡقَلَمِۙ—عَلَّمَ الۡاِنۡسَانَ مَا لَمۡ يَعۡلَمۡؕ

Read in the name of your Lord—Who created man from a clot of congealed blood—Recite: and your Lord is Most Generous—Who taught by the pen—taught man what he did not know. Quran [96:1-5]

This was the very first revelation that the prophet received from the angel Jibreel. The Prophet was held in fear and returned to his wife, Khadija, trembling and asking her to cover him. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was in a condition of continuous terror, and he said to Khadija, I do not know what is wrong with me; I fear that something might happen to me.

The wife of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Khadija, consoled him with her kind words and said; Fear not! I swear by Allah that He will not disgrace you, as you are kind to your close ones, you speak the truth, you help the poor, and you are bountiful to your guests.

The beloved wife of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) took the responsibility to calm down the prophet, for this purpose, she took the prophet to her cousin, whose name was Warqa ibn Nawfal.

He was an old, generous man who converted to Christianity before Islam, and he knew the language of the holy scriptures (Torah and Injeel), and he used to translate those holy scriptures into Arabic.

After listening to his cousin Khadijah, he asked the prophet, What do you see, O my nephew? The prophet explained everything that happened in the cave of Hira. Warqa said; This is the same entity whom Allah sent to the prophet Moses. Warqa said I wish I were young and could support you when your people turn you out. He added that every man who came with the same message as you faced these difficulties from their people.

But after a few days, Warqa died and could not live, and the divine revelation to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) paused for some time. The prophet felt so grieved and overwhelmed that several times Jibreel would descend to calm down and support the prophet of Allah.[34]

This is how the first revelation was revealed. The importance of the first revelation could be observed from the verses where the orders of reading were given to an unlettered man in the sandy dunes of Arab in the cave of Hira.

Every prophet was bestowed with miracles related to the issues of their times. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was bestowed with the miracle of rhetoric and fluency, The eloquence of the Quran was a challenge for the Arabs and the same challenge stands until the day of judgment.

As reported by Abu Hurairah;

The prophet said; every prophet was given miracles, because of which people believed them, but I was given the miracle of divine revelation.[35]

The Quran itself is a testimony that no human could have penned it due to its eloquence and rhetoric.

Teaching The Quran

History recorded the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) as an unlettered person, like the vast majority of people during his time and his area, from which we can conclude that Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) did not know how to read and write.

According to Bukhari and other sources, the companion and cousin of the prophet Ali ibn Abi Talib wrote the treaty of Hudaibiyah.[36]

The first revelation is proof that Allah commanded a reading policy to educate not only himself but also the populace at the time.

The first revelation stated that;

اِقۡرَاۡ بِاسۡمِ رَبِّكَ الَّذِىۡ خَلَق

Read! In the name of your Lord, who created! Quran [96:1]

After the revelation of this order by Allah, the prophet of Allah took every step to spread the importance and rise of the spirit of education to his companions.

As reported by Abdullah ibn e Mas’ud and Abu Hurairah;

The prophet said, Acquire knowledge and impart it to the people.[37]

Another hadith reported by Abu Hurairah;

The Prophet said; whoever takes a path upon which to obtain knowledge, Allah makes the path of paradise easy for him.[38]

On the other hand, Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) warned those who had the intention of hiding knowledge to themselves only,

The prophet said that those people; who are asked about something and that person hide the knowledge would be punished with a bridle of fire placed around him on the day of resurrection.[39]

All of these commands resulted in growing Madinah as a city of Knowledge, wisdom, and command. The policies of the education system were developed at the very beginning of the state of Madinah.

Students of Suffah (enclosure);

Ubadah bin Samit was one of the companions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), He used to teach the people of Suffah without any cost, as free education was provided for everyone, and the Prophet of Allah strictly commanded him not to accept anything from the students of Suffah.[40]

Suffah was an enclosure that was connected to the prophet’s mosque and provided shelter and food to the poor. It also served as a regular residential school for the companions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). It was also a learning center for day scholars and visitors in large numbers.

The prophet of Allah required the literate people at the state level to communicate with other heads of state.

Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) commanded Zaid bin Sabit to learn Hebrew.[41] Zaid bin Sabit knew a lot of other languages, like Persian, Greek, and Ethiopian, and he was the one who used to read and write letters for the prophet.

This atmosphere of spreading and seeking knowledge made the world look to them for guidance.

Incentives For Education of Quran

The prophet of Allah practically created an atmosphere of seeking knowledge and spared no part for ignorance among his companions. The mindset of gaining knowledge was important to understand the wisdom of the Quran. That is why seeking knowledge of the Quran and spreading it to the people was above all the other rewards. Even knowledge without the wisdom of the Quran is of no use.

Learning the Quran;

Reported by Uthman bin Affan:

The best among you is the one who learns the Quran and teaches it to the people.[42]

Reported by Ibn e Masud;

The prophet said that if anyone recites a letter from the book of Allah, then he will be credited with a good deed, i do not say that Alif, Lam, and Meem are one letter, but Alif is a letter, Lam is a letter, and Meem is a letter.[43]

These two references from the Hadith show the importance of learning, reading, and teaching the Quran. Every letter of the Quran contains virtues and blessings for its readers.

The Quran is a crucial part of prayer, and it was necessary for the Muslims to learn it and lead their fellow Muslims in prayer, At that time, among the companions, the one who learned the Quran was considered to have a great level of wisdom and virtue.

As reported by Anas bin Malik:

The person who has memorized or learned the Quran the most will lead in the prayer.[44]

In another Hadith report, Amr bin Salima al-Jamri recounts that the people of his tribe came to the prophet and embraced Islam. Before departure, they asked the prophet, who would lead us in the prayer. The prophet replied to the one who knows the Quran the most.[45]

During the illness of the prophet, Abu Bakr was ordered by the prophet to lead the prayer in his absence.[46] It shows that the prophet considered Abu Bakr one of the people who knew the Quran.

Learning the Quran and seeking wisdom through its teachings gives one the privilege of gaining higher ranks in this world and hereafter.

The knowledge of the Quran is the basis for appointing a caliph for the Muslims. This criterion was followed by the companions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) after his death, and Abu Bakr was appointed as the first caliph of the Muslim world. The book of Allah is a scale to measure the Taqwa and wisdom of a person.

Umar bin al-Khattab reported that the prophet said; with this book, Allah exalts some people and lowers others.[47]

And the book of Allah is such a precious treasure that every Muslim should struggle to gain wealth from this book by pondering over it, it is legitimate for the people to compete in gaining the wisdom of this book.

Narrated Ibn Mas’ud: I heard the Prophet saying, There is no envy except in two: a person whom Allah has given wealth and he spends it in the right way, and a person whom Allah has given wisdom (i.e., religious knowledge) and he gives his decisions accordingly and teaches it to the others.[48]

Memorizing was the massive source of preserving the Quran so during the writing process of Quranic scripture, people were motivated to memorize the Quran. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) gave glad tidings even for those who were facing difficulties in memorizing the book of Allah.

People who memorized the Quran by heart were called Huffaz, which means the preservers of the Holy Book. They were promised tremendous rewards, As reported by Abdullah bin Amr, the prophet said; The one who was devoted to the book of Allah will be told on the day of judgment to recite and ascend, and to recite with the same care he practiced while he was in the world, for he will reach his abode in the heavens with the last verse he recites.[49]

The Quran was a source of purifying the hearts of those who were prone to idleness from past generations. People were prompted to learn the Quran and seek guidance through it to leave the ignorance of Jahiliya.

As reported by Ibn Abbas, the prophet said; A person who has nothing in his heart from the Quran is like a ruined house.[50]

The prophet also forbade memorizing the Quran and later forgetting it, and he advised people to read it frequently.

As reported by Abu Musa al-Ashari, the prophet said, Keep refreshing the knowledge of Quran; I swear by Him in Whose hand is the life of Muhammad that it is more liable to escape than hobbled camels, (forgetting the Quran).[51]

The following narration demonstrates the care that the Prophet took in teaching the Quran: “Whenever a person immigrated to Madinah, the Prophet would assign him to one of us so that we could teach him the Quran,” according to Ubaadah ibn as-Saamit. Eventually, the masjid became so noisy because of all of this recitation of the Quran that the Prophet ordered us to lower our voices so as not to distort the meaning (by mixing all of these verses).”[52] Therefore, the Prophet would ensure that each new Muslim had a teacher to teach him the Quran.

Such was the concern of the Prophet in teaching the Quran to the new Muslims that he would even send companions to other cities to ensure that the Muslims in those cities could memorize the Quran. Even before the hijrah, the Prophet sent two companions, Ibn Umm Maktum and Mus’ab ibn ‘Umayr, to teach the Muslims of Madinah the Quran. After the hijrah, the Prophet sent Maaz bin Jabal to Makkah to teach the Quran to those who had not been able to perform the hijrah.[53]

Writing the scripture during the life of the prophet;

During the later periods, the Prophet also made sure that the Quran was written down, and not just memorized. Al-Bukhaaree reports the following story:

When it was revealed:

لَا يَسۡتَوِى الۡقَاعِدُوۡنَ مِنَ الۡمُؤۡمِنِيۡنَ غَيۡرُ اُولِى الضَّرَرِ وَالۡمُجَاهِدُوۡنَ فِىۡ سَبِيۡلِ اللّٰهِ

«Not equal are those believers who sit at home and those that strive in the

cause of Allah … > Quran [4:95]

The Prophet said, ‘Call Zayd ibn Thaabit for me, and tell him to bring the ink-pot and the scapula bone (i.e., paper and pen).’ When Zayd came, the Prophet told him, ‘Write: “Not equal are those believers who sit at home and those … (to the end of the verse)”.[54]

In another report, Zayd narrates, “I used to write the revelation for the Prophet while he dictated to me. When I finished [writing], he would tell me, ‘Read [what you wrote]’ so I read it. If something was missing, he would fix it.”[55]

The Companions also had their copies of the Quran. The Prophet had commanded the Companions, “Do not write anything from me except the Quran. Whoever writes anything besides the Quran should burn it.”[56] However, this command was later abrogated by him, for he later allowed the Companions to write down hadith also.[57] So common were these Mushafs that the Prophet had to issue an order prohibiting the Companions from traveling to enemy territories with copies of the Quran, for fear that these Mushafs might fall into enemy hands and thus be disrespected.[58]

Those Companions who were famous for their Mushafs were Ubay ibn Ka’ab, ‘Abdullah ibn Mas’ood, ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, and some of the wives of the Prophet, among them ‘Aishah and Hafsa. Some sources have listed over fifteen companions who were recorded to have written down most of the Quran.[59] These were not complete copies of the Quran, nor was the arrangement of the Surahs in them the same as the later arrangement. For example, Ibn Mas’ood had one hundred and six Surahs, and the order of the Surahs was not the order that is present today. Ubay ibn Ka’ab also had less than one hundred and fourteen Surahs, and, in addition to the Surahs that he had, the prayer for qunoot (A prayer that is meant to be recited in the Witr prayer) and a hadith are also found.

‘Scholars’ who try to cast doubts on the authenticity of the Quran use such narrations to try to prove that these additions were verses’ that were left out of the Quran, but it should be remembered that these copies were for personal use, and as such, the Companions could have written any knowledge besides the Quran that they wished to preserve. Az-Zarqaanee writes:

To summarize, some Companions who used to write the Quran in personal Mushafs sometimes wrote material that was not a part of the Quran. This material might be interpretative clauses for certain obscure phrases in the Quran, prayers (duas), or other similar things. They were fully aware that these additions were not part of the Quran. However, because of the scarcity of writing materials, and since the Mushafs were for personal use, they wrote these additions in the Mushaf since there was no fear of them mixing the additions that they had written with the text of the Quran. Those people of little intellect fail to take these factors into account and assume that these additions were a part of the Quran, even though this was not the case.[60]

It was the practice of the Prophet to recite the Quran to the Angel Jibreel every year, during the month of Ramadan, and Jibreel would also recite it back to him. Faatimah, the daughter of the Prophet, reported that the Prophet told her, “Jibreel used to recite the whole Quran to me every Ramadan, but this year he has recited it to me twice. I do not see (any explanation for this) except that my time (of death) is near.”[61] In another narration, ‘Aishah added, “The Prophet used to meet Jibreel every night of Ramadan and recite to him the Quran.”[62] Therefore, the Prophet used to recite the Quran to Jibreel and used to hear Jibreel’s recitation also, and the year that he died, he recited the Quran twice to Jibreel and heard it from Jibreel twice. During this last recitation, Zayd ibn Thaabit was present.

The Prophet (s) did not compile the Quran in one book during his lifetime, nor did he command the Companions to do so. He made sure that the Quran was written down in its totality, but he did not order for it to be compiled between two covers. There are several reasons for this:

- There was no pressing need during the lifetime of the Prophet to compile the whole Quran in one book since the Quran was not in any danger of being lost. Numerous companions had memorized all of it, and each companion had memorized various portions of it. We will discuss this topic in more detail later.

- During the lifetime of the Prophet, the Quran used to be continually revealed. Therefore, it would not have been feasible to compile all of it in one book since it had not been completely revealed yet. The last verse was revealed only nine days before the death of the Prophet.

- The arrangement of the verses and surahs was not chronological. Verses that were revealed years after the hijrah could be placed, by the command of the Prophet, amid Makkan verses, and vice versa. Therefore, the Prophet could not have compiled the Quran in the correct order until all its verses had been revealed.

- Some revelations used to be a part of the Quran, but Allah abrogated their recitation. During the lifetime of the Prophet, this abrogation could occur at any time; therefore, the Wahy (Revelation) needed to be terminated before the Quran be compiled.

To summarize, when the Prophet passed away, the entire Quran had been memorized by many of the Companions and existed in written form, but it had not been compiled between two covers. Rather, it was scattered in loose fragments that were owned by different people. Some Companions also had substantial (yet incomplete) copies of the Quran.

The First Compilation

Following the Prophet’s death, his closest followers chose Abu Bakr as their leader. His first challenge was dealing with apostasy. During the Prophet’s life, some individuals converted to Islam mainly for political benefits. Once the Prophet passed away, they rejected the new Islamic leadership. Many of these individuals pledged their loyalty to self-proclaimed prophets. To unify the Muslim community, Abu Bakr launched a series of conflicts known as the ‘Wars of Apostasy.’

During one of these battles, the Battle of Yamama (12 A.H.), around seventy Companions who had memorized the Quran were martyred. The death of such a large number of qurraa’ (memorizers of the Quran) alarmed ‘Umar, and he went to Abu Bakr and said, “Many of the memorizers of the Quran have died, and I am scared lest more die in later battles. This might lead to the loss of the Quran unless you collect it.” ‘Umar not only realized the danger of this great loss but also proposed a solution.

Abu Bakr replied, “How can I do that which the Prophet did not do?” Abu Bakr, the one whom the Prophet trusted the most in all his affairs, could not even think of undertaking a project that the Prophet had not done, nor ordered to be done. He was worried that such a project might be considered an innovation in religion.

But ‘Umar continued to convince him, exhorting him of the merits of such an idea, and proving to him that such a project was in no way an innovation. ‘Umar realized that this act did not qualify as an innovation in the religion, since the compilation of the Quran was not a religious act per se, but rather an act that was of general benefit (maslaha) to the Muslims. He continued to convince Abu Bakr until Abu Bakr understood Umar’s arguments and agreed to the project. They both decided to put the Companion Zayd bin Thaabit in charge of collecting the entire Quran in one manuscript. Abu Bakr told him, “You are an intelligent young man, and we do not doubt you. You used to write the revelation for the Prophet, so we want you to collect the Quran.”[63]

They chose Zayd because he was the person best suited for the job, for the following reasons:

- Zayd ibn Thaabit served as the Prophet Muhammad’s main scribe. This role was so significant that Abu Bakr remarked, “You used to write the revelation for the Prophet.” This is further evidenced by a narration in al-Bukhaaree, where the Prophet specifically asked for Zayd. After the Prophet’s death, some people approached Zayd and requested him to share something from the Prophet. He replied, “And what can I narrate to you? I used to be a neighbor of the Prophet, and whenever he received revelation, he would call me to write it.”[64] Hence, Zayd was the person entrusted by the Prophet with recording the Quran.

- During the Prophet’s lifetime, Zayd collected the Quran. Anas ibn Maalik mentioned that only four people had collected the Quran before the Prophet’s death: Ubay ibn Ka’ab, Mu’adh ibn Jabal, Zayd ibn Thaabit, and Abu Zayd.[65]

- Being younger than many of the Companions, Zayd ibn Thaabit had a sharper memory. He recounted that at eleven years old, shortly after the Prophet arrived in Madinah, he was brought before the Prophet. The people said, “O Messenger of Allah, this is one of the boys of Banee an-Najjaar, and he has memorized seventeen surahs.” Zayd recited to the Prophet, who was very pleased with his recitation.[66]

- Zayd was also present during the Prophet’s final recitation to Jibreel in Ramadan before the Prophet’s passing. According to the well-known successor, Abu ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan as-Sulami (d. 70 A.H.), Zayd’s presence at this significant event led Abu Bakr to rely on him for the Quran’s initial compilation. Later, Uthman assigned him the crucial task of overseeing the second compilation.[67]

- Zayd ibn Thaabit was highly esteemed among the Companions for his exceptional knowledge of the Quran’s recitation. Sulayman ibn Yasaar (d. 100 A.H.) noted that neither ‘Umar nor ‘Uthman held anyone in higher regard than Zayd concerning the laws of inheritance and Quranic recitation. ‘Aamir ibn Sharaheel ash-Sha’bee (d. 103 A.H.) remarked that Zayd’s mastery of Quranic recitation and inheritance laws made him a dominant figure in these fields. His prominence was such that ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and ‘Ali, all entrusted him with significant judicial and recitational duties in Madinah, a role he fulfilled until he died in 45 A.H. Upon his passing, Ibn ‘Umar expressed his respect by saying, “May Allah have mercy on him! He was a scholar among the people.” Despite sending scholars to various regions, Umar kept Zayd in Madinah to oversee judicial matters for its residents.[68]

It was no surprise that Abu Bakr and ‘Umar saw Zayd ibn Thaabit as the right person for the significant task of compiling the Quran. Zayd had all the necessary qualities for this monumental job, though he was initially reluctant. Only after both Abu Bakr and ‘Umar persuaded him did he agree, remarking, “It would have been easier for me to move a mountain than do what they asked of me.”

Zayd began by gathering the various fragments of the Quran from pieces of wood and people’s memories. He required at least two individuals, aside from himself, who had directly learned the verses from the Prophet, and one written copy of the verse made under the Prophet’s supervision, to ensure its inclusion in the final compilation. ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattab announced in the mosque, “Whoever has learned any Quran from the Prophet, let him bring it forth.”[69]

The people brought their scraps and parchments of the Quran to Zayd ibn Thaabit. Abu Bakr instructed them, “Sit at the door of the mosque. Whoever brings you two witnesses (for a verse), then write it down.” Some scholars interpret this to mean two witnesses and two written copies were needed.

Zayd reports, “I collected the Quran, until I found the last two verses of Surah at-Taubah with Khuzaymah ibn Thaabit al-Ansaaree:

لَـقَدۡ جَآءَكُمۡ رَسُوۡلٌ مِّنۡ اَنۡفُسِكُمۡ

«There has come to you, from among yourselves, a Messenger …~ Quran |9:128|

I found these verses with him only.”[70] The report about Khuzaymah does not imply he was the only one who heard the verse from the Prophet, but rather that he was the only one who had a parchment with the verses written on it. When Khuzaymah presented his parchment, ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affaan said, “I testify that these verses have been revealed by Allah!”[71]

Zayd’s strict criteria ensured the Quran’s authenticity. Despite having memorized the entire Quran, he required at least two other memorizers of each verse and a written copy made under the Prophet’s supervision. The story of Khuzaymah indicates Zayd was searching for the last two verses of Surah at-Tawbah. Though Zayd had heard them from the Prophet, no one else had provided written copies until Khuzaymah did. Another narration adds, “I could not find a verse that I used to hear from the Prophet until I found it with a person from the Ansaar, and I did not find it with anybody else.”

مِنَ الۡمُؤۡمِنِيۡنَ رِجَالٌ صَدَقُوۡا مَا عَاهَدُوا اللّٰهَ عَلَيۡهِ

“among the Believers are men who have fulfilled their covenant with

Allah» Quran [33:23],

so, I put it in its proper Surah.”[72] This narration also proves the fact that Zayd knew what was part of the Quran and what was not, since he mentioned that he was searching for a particular verse, and could not find it. It also proves that the arrangement of the verses was known to the Companions, because he put the verse ‘in its proper surah and also proves that now, for the first time, the Quran is in one book. Barely two years after the death of the Prophet, when all of the major Companions were still alive, the Quran had been compiled. The written copy of the Quran was called a Mushaf (literally meaning a collection of loose papers) and remained with Abu Bakr and, after his death, with ‘Umar, then with Hafsah, the daughter of ‘Umar and a wife of the Prophet.

The Mushaf that Abu Bakr ordered to be collected was not meant to be an official copy that the whole ummah had to follow. Rather, it was meant to preserve the Quran in its entirety and ensure that none of its verses were lost. In this, Abu Bakr accomplished a momentous task. ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib remarked, “The person with the greatest rewards with regards to the (compilation) of the Mushaf is Abu Bakr. May Allah’s mercy be on Abu Bakr, he was the first person to compile the Book of Allah.”[73] The claim by certain Islamic sects that ‘Ali was the first to compile the Quran is shown to be false by a narration from ‘Ali himself. Furthermore, the narration which mentions ‘Ali as being the first is weak.[74]

There is some difference of opinion over the arrangement of the Surahs in Abu Bakr’s Mushaf. Most scholars think that Abu Bakr’s Mushaf did not concern itself with the proper order of the Surahs, for it was not meant to be an official copy that was binding upon the ummah. Others allege the Surahs were in the same order as that of ‘Uthman.

The ‘Uthmanic Compilation

After the death of Abu Bakr, ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattaab took over the leadership of the Muslims. Under his auspicious caliphate, the territories of the Muslims expanded five-fold what they had been. When he passed away, the Muslims controlled the remnants of the Persian Empire, Egypt, Syria, and parts of the then-defunct Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. After ‘Umar’s death, ‘Uthman took over the caliphate and continued the great legacy of his two predecessors. The Muslims were successful in waging jihad for the cause of Allah and spreading the religion of Islam. One of the places where this was occurring was in the territories of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Muslims from different parts of the ummah had joined forces to fight against the enemy.

Unfortunately, the Muslims started differing among themselves about the recitation of the Quran. The Muslims from Syria were reciting the Quran differently than the Muslims from Iraq. They began contending with each other, each regarding his recitation superior to his brother’s. These Muslims were not companions and therefore were not trained in the proper manner and etiquette of the recitation of the Quran. One of the companions who was present among them, Hudhayfah ibn al-Yamaan, could not believe what was happening. He advised them to leave this argumentation, but he realized that some action must be taken to prevent this occurrence on a larger scale. He therefore left Azerbaijan for Madinah to report to the caliph ‘Uthman.

“O Commander of the Faithful!” Hudhayfah pleaded to ‘Uthman, “Save this ummah before it disagrees with its Book like the Jews and Christians did before it.”[75] Hudhayfah told ‘Uthman what had occurred among the new Muslims in Azerbaijan. ‘Uthman, alarmed by this news, convened a gathering of the leading companions. He informed them of what Hudhayfah had told him and requested their advice on this matter. The Companions, in return, asked ‘Uthman what he thought the best plan of action was. ‘Uthman told them his opinion: Official copies of the Quran should be written and sent to all the provinces, and all other copies destroyed so that the ummah would have one standard Quran. Therefore, this standard version would serve to unite the Muslims upon one recitation.

‘Ali ibn Abi Talib said concerning this incident, “O People! Do not say evil of ‘Uthman, but only say good about him. Concerning the burning of the Mushafs, I swear by Allah, that he only did this after he had called all of us. He asked us, ‘What do you think (should be done) concerning these recitations (in Azerbaijan)? For it has reached me that each party is claiming that their recitation is better, and this (attitude) might lead to disbelief.’ We asked him, ‘What do you suggest we do?’ He responded, ‘I think we should consolidate the Muslims on one Mushaf so that there would not be any disagreements or disunity.’ We said, ‘Verily, this idea of yours is an excellent idea.’[76] All of the companions approved of Uthman’s action.

Therefore, after the Companions agreed to his idea, he requested Hafsah, the daughter of ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattab, to loan him the Mushaf that Abu Bakr had ordered to be compiled, which she did. He then chose a committee of four people, namely Zayd ibn Thaabit, ‘Abdullah ibn az-Zubayr, Sa’eed ibn al-‘Aas, and ‘Abd al-Rahmaan ibn al-Haarith, to rewrite the Mushaf of Abu Bakr. He chose Zayd ibn Thaabit for the same reasons that Abu Bakr had done before him, and Sa’id ibn al-As was known for his knowledge of the Arabic language. Imam adh-Dhahabi (d. 748 A.H.) said, “Sa’eed ibn al-‘Aas was one of the members of the committee whom ‘Uthman chose to write the Mushaf, due to his eloquence, and because his (Arabic) style was very similar to the Prophet’s.”[77] The other two members were respectable Companions, knowledgeable of the Arabic language and the Quran.

Apart from Zayd, the other three committee members were from the Quraysh. This was done on purpose; ‘Uthman told them, “If you (three) and Zayd differ (on how to spell a word), then spell it in the dialect of the Quraysh, for verily it was revealed in their dialect.”[78] ‘Uthman said this in response to a difference that arose among them concerning the writing of the word ‘Tabut’ (in 2:248): should they write the word in the Quresh style of Tabut (i.e with taa marbuta) or the Madni style of Tabuh (i.e with Taa Taneeth)? ‘Uthman answered them that they should write it as Tabut since this was the style of the Quraysh.

This incident shows that the committee consulted the other companions concerning even such minor details as the spellings of certain words. At times, when there was a difference of opinion, they even called that particular scribe (if it happened to be other than Zayd), who had written the verse for the Prophet, so that they could ask him how he had spelled the word.[79]

After the committee finished its task, ‘Uthman ordered that one copy of this Mushaf be sent to every province, and ordered the governors of each province to burn all the other copies of the Quran in their provinces. This was a drastic step, but it was necessary if the unity of the Muslims was to be preserved. Every Quran written after this time had to conform letter for letter to ‘Uthman’s Mushaf. By his wise decision, ‘Uthman provided a copy of the Quran that would serve as a model for all future Mushafs. And, as ‘Ali pointed out, ‘Uthman did this with

the approval of the Companions. Although there are some reports that initially ‘Abdullah ibn Mas’ood did not agree with ‘Uthman’s decision, it is also reported that he later changed his mind.[80] According to the famous historian, Ibn Katheer, ‘Uthman wrote to Ibn Mas’ood advising him to follow the consensus of the other Companions, which he agreed to do.[81] In fact, ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib said, “If I were in charge (of the affairs of the Muslims) when ‘Uthman had been, I would have done the same as he did.”[82]

Not only did ‘Uthman send the actual Mushafs to each province, but he also sent Quranic reciters to teach the people the correct recitation of the Quran. He kept Zayd ibn Thaabit in Madinah; with the Makkan Mushaf, he sent “Abdullah ibn Saa’ib (d. 63 A.H.); to Syria was sent al-Mugheerah ibn Shu’bah (d. 50 A.H.); Abu ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan as-Sulami (d. 70 A.H.) was sent to Koofah; and ‘Aamir ibn ‘Abdul Qays to Basra (d. ~55 A.H.).[83] All of these reciters were well-known for their recitation of the Quran, and it is in fact through them that most of the qira’at are preserved.

‘Uthman’s compilation occurred in the year 24 A.H., or, according to others, in the early part of 25 A.H.[84]

Abu Bakr’s compilation of the Mushaf differed from ‘Uthman’s compilation in the following ways:

- The reason that each of them compiled the Quran was different. Abu Bakr compiled the Quran in response to the large number of deaths of those who had memorized the Quran, and in fear of its being lost. ‘Uthman, on the other hand, compiled the Mushafs in response to the inauthentic recitations that newcomers to Islam, who were ignorant of the Arabic of the Quran, were reciting. He wished to unite the Muslims in the proper recitation of the Quran and therefore ordered the eradication of all other Mushafs so that the people would have only one Mushaf in their hands.

- The number of people who were in charge of the two compilations was different. Abu Bakr relied on the person who was the best suited and most qualified to do so, namely Zayd ibn Thabit. ‘Uthman, on the other hand, used the services of Zayd but also had three of the major Companions, all of whom were known for their knowledge of the Quran, to help him.

- The number of Mushafs Abu Bakr ordered to be made was only one, whereas ‘Uthman ordered several.

- Since Abu Bakr did not face the problem of inauthentic recitations of the Quran, he did not have to take the step that ‘Uthman did in destroying all other written copies of the Quran. Uthman’s decision ensured that all future copies would have to rely upon the original ‘Uthmanic ones.

- Abu Bakr compiled the Quran from ‘ … date palm leaves, wood and the hearts of people … ‘ whereas ‘Uthman ordered the rewriting of Abu Bakr’s Mushaf in the writing style of the Quraysh.

- Abu Bakr’s Mushaf, according to one opinion, did not concern itself with arranging the Surahs properly; only the verses of each Surah were arranged. ‘Uthman, on the other hand, arranged the Surahs and verses in their proper arrangement.

To summarize, we can say that in the year that the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) passed away, Jibreel went over the Quran with him twice, and this last rehearsal is the recitation of Zayd ibn Thaabit and others, and it is the recitation that the Khulafaa ar-Rashidoon, Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and ‘Ali ordered to be written in Mushafs, and Abu Bakr was the first to write it. Then ‘Uthman, during his caliphate, ordered it to be written again, and he sent it to all of the provinces, and the Companions all agreed to this.”

Differences

As we already discussed, there are differences between the Mushaf of Abu Bakr and the Mushaf of Uthaman. Now we will discuss general differences, which are in a lot of different Mushaf, which does not affect its preservation, but still, it is necessary to know the differences so we will get a broad and detailed idea about them, and this also makes it easy to understand the differences that occurred in the manuscripts of the Quran, which we will discuss in another chapter.

The Spelling of the Words of the Quran

The spelling of the words of the Quran is not the same as the spelling of modern-day Arabic. There are certain peculiarities of the ‘Uthmanic script that are not present in modern Arabic. Among these peculiarities in the writing of the Mushaf is that the ‘Uthmanic script eliminated certain alifs (for example the word ‘Rahman’ is written without an alif); and added certain silent letters (for example the word ‘salat’ is written with a silent waw); merged particular words (for example when the word ‘min’ is followed by ‘maa’ it is usually written as one word ‘mimaa’); and occasionally spelled the same word that occurred in different places differently.[85] Some of these peculiarities were common in Arabic and specifically the Qurayshi script of that time, but later Arabic grammar changed these rules.

Another peculiarity was that when there existed two recitations of a particular word, the word was written such that both recitations would be preserved. For example, The word Maliki in 1:4 is written without an Alif i.e Maliki: مٰلك Since the alternate recitation Maliki had the alif has been written on this word i.e Maliki: مالک, the second recitation would not have been possible from the Mushaf of ‘Uthman; however, by writing it without an alif, both recitations are possible. The nature of the Arabic script and manner of writing allows for this, in contrast to Latin-based languages.

The Script of the Mushaf

The script of the Arabic is the style of writing of the various letters. For example, the font with which this text is written differs from the font of the chapter title. The script, then, is the style with which the letters are written. This is to be differentiated from the spelling, which was the topic of the previous section.

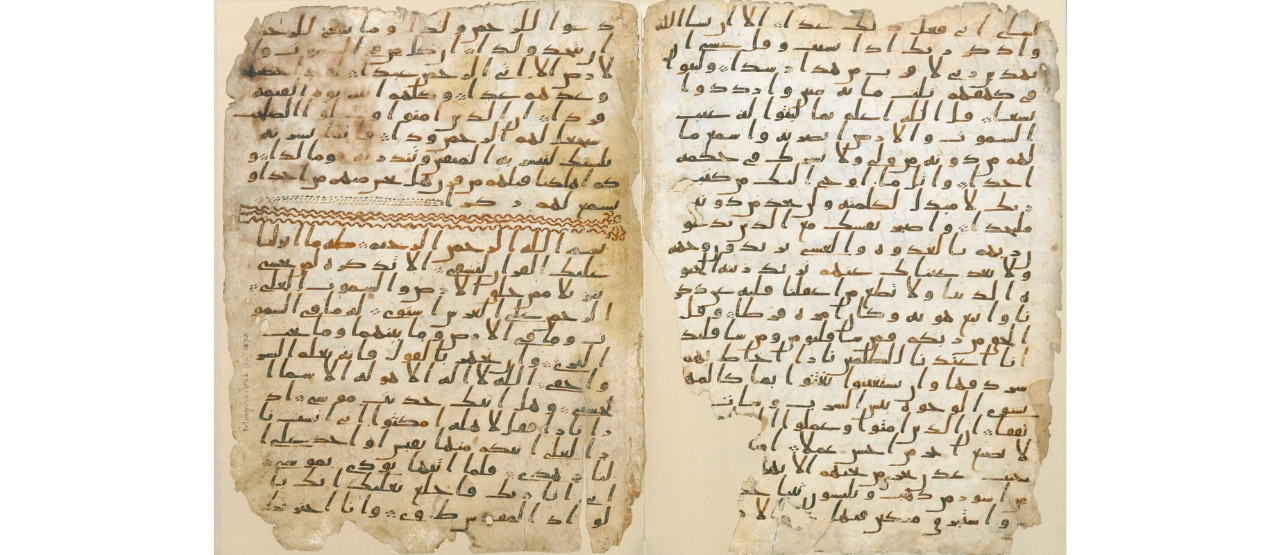

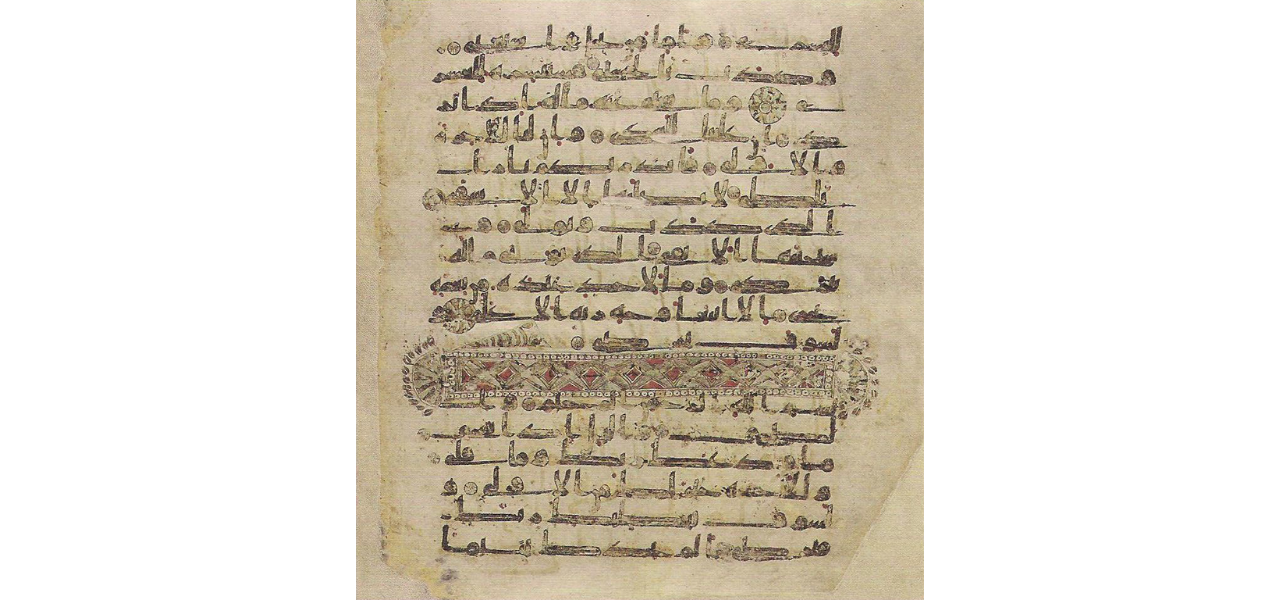

The script in which the ‘Uthmanic Mushaf was written was the old Koofee script. This script is almost incomprehensible to modern-day Arabic readers. The Mushafs were written without any hamzahs, dots (Nuqat – The nuqaat are the dots that are used to differentiate between different letters that have the same base structure; for example, the only way to differentiate between the letters yaa and taa is by the dots: if two dots are above the line, it is a taa, and if they are below, it is a yaa) or vowel marks (Tashkeel – The taskheel of the Quran are the diacritical marks of fat’ha, Kasra, and dhamma (in Urdu, the zeer, sabar, and Pesh), and other marks (such as the shadda) that are used to pronounce the particular letters correctly). This was the traditional manner of writing at that time. Therefore, for example, a straight line could represent the letters baa, taa, thaa, and yaa, and each letter could have any of the vowel marks assigned to it. It was only by context that the appropriate letters and vowels could be differentiated. The Arabs at that time were accustomed to such a script and would substitute the appropriate letter and vowel depending on the context.

The ‘Uthmanic Mushaf was arranged in the order of the Surahs present today. No indications were signifying the ending of the verses, and the only sign that a Surah had ended was the bismillah (The phrase ‘Bismillah al-Rahmaan al-Raheem’, which appears at the beginning of each Surah except the ninth). There were also no textual divisions (into thirtieths, sixtieths, etc.). This was done so that the Quran be preserved with the utmost purity; only the text of the Quran, unadorned with later embellishments, was written.

This was the appearance of the original ‘Uthmanic Mushafs. As is well-known, however, the appearance of modern Mushafs is strikingly different from the simple Uthmanic one. The process of this change was gradual.

The first change to occur was the addition of the diacritical marks to the tashkeel. There are varying reports as to who the first person to add Tashkeel to the Quran was.

The name that is most commonly mentioned is that of a Successor by the name of Abu al-Aswad ad-Du’ali (d. 69 A.H.), who was also the first to codify the science of Arabic grammar (Nahw). According to one report, ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib asked him to make the Mushaf easier for the people to recite, but he initially declined to do so, since he did not believe it was necessary. However, he once heard a person recite the verse,

اَنَّ اللّٰهَ بَرِىۡءٌ مِّنَ الۡمُشۡرِكِيۡنَ وَرَسُوۡلُهٗ.

“Allah and His Apostle break off all ties with the pagans.” Quran [9:3]

as “Allah breaks off all ties with the pagans and His Apostle.” This drastic change in meaning occurred by changing only one vowel (i.e., pronouncing rasooluh as rasoolih). Said Abu al-Aswad, “I did not think the state of the people had degenerated to this level!” Recalling the advice of Ali ibn Abi Talib, he went to Ziyaad ibn Abeehee, the governor of Iraq under ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, and requested him to supply him with a scribe. Abu al-Aswad told the scribe, “If I pronounce (the vowel) a, then write a dot above the letter. If I pronounce it as u, then write a dot in front of the letter. If I pronounce an i, then write it below the letter.”[86] Abu al-Aswad was reacting to the problems that had arisen among non-Arabs who had embraced Islam and were new to the Arabic language. They had difficulty reading the script of Uthman, without a tashkeel. Thus, Abu al-Aswad started the rudimentary art of tashkeel.

Other reports give the names of Nasr ibn ‘Aasim (d. 89 A.H.), Yahya ibn Ya’mar (d. 100 A.H.), al-Hassan al-Basree (d. 110 A.H.), and Muhammad (PBUH) ibn Seereen (d. 110 A.H.). However, some of these reports qualify Nasr and Yayha as adding the dots (nuqat) for the first time, and not the tashkeel. Yet another report states that it was Abu al-Aswad who was the first to do this, but at the command of Hajjaaj ibn Yoosuf (d. 95 A.H.), the infamous governor of Iraq under the fifth Umayyad Caliph, ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwaan, and not under the caliphate of Ali.

In combining all of these reports, the strongest series of events seems to be as follows: Abu al-Aswad was the first to add the tashkeel into the Mushaf on an official basis, during the caliphate of Ali, and his students Yahya ibn Ya’mar and Nasr ibn ‘Aasim were the first to officially add dots (nuqat) during the reign of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwaan (d. 86 A.H.). They were not the first to do so, however, as both al-Hassan al-Basree and Muhammad (PBUH) ibn Seereen had preceded them in this endeavor. However, al-Hassan al-Basree and Muhammad (PBUH) ibn Seereen had added the nuqat on their private Mushafs, whereas Abu al-Aswad and his two students were the first to add the taskheel and nuqat on an official basis into the Mushaf. This sequence of events takes into account all of the narrations and is the one that most of the researchers in this field have concluded.[87] Az-Zarqaanee writes,

May Allah have mercy on these two scholars (Yahya ibn Ya’mar and Nasr ibn ‘Aasim), for they were successful in this endeavor (of adding nuqat to the Quran), and completed the addition of the nuqat for the first time. They conditioned upon themselves not to increase the number of dots of any letter above three. This system spread and became popular among the people after them, and it had a great impact in removing confusion and doubts concerning (the proper recitation of) the Mushaf.[88]

Thus, Abu al-Aswad was the first to add the tashkeel to the Quran, and Yahya and Nasr were the first who differentiate the various similar letters of the Arabic alphabet using dots. They did this during the reign of the Ummayad Caliph ‘Abd al-Maalik.

Abu al-Aswad died in 69 A.H., and ‘Abd al-Maalik’s reign ended in 86 A.H., which means that less than three-quarters of a century after the Prophet’s death, while some of the Companions were still alive, the Quran had been written down with a rudimentary version of tashkeel and nuqat.